Dorothea Baltruksa, Maren Sowab, Maike Vossa,*

a) Centre for Planetary Health Policy, Berlin

b) Maren Sowa is a research assistant and doctoral student at the Chair of Civil Law, Medical and Health Law of Prof. Dr. Jens Prütting. Prütting is the Managing Director of the Institute for Medical Law at Bucerius Law School

* Authors in alphabetical order

We would like to thank Robert Schulz, Anja Leetz and Esther Luhmann for their kind support.

Policy Brief 01–2023

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7682082

The impact of the climate crisis on our well-being and health becomes more apparent with every heatwave, extreme weather event and drought. But other environmental damages caused by human activities also have a direct and indirect impact on our health. In particular, the dramatic loss of biodiversity and the pollution of water, air and soil have long surpassed safe levels.1 Health protection does not therefore only belong in health policy, just as environmental protection must reach far beyond environmental policy.

On the one hand, the pharmaceutical industry plays an essential role in health care with its important health-protecting and health-promoting products. On the other hand, its chemical-intensive production contributes significantly to environmental and climate pollution, which in turn damages our health and livelihoods. In this policy brief, we take a closer look at these problems and show which legal levers can be used to improve the environmental and climate impacts of the sector. We see the following as particularly effective levers: an environmental risk assessment for the authorisation of medicinal products for human use; the mandatory inclusion of sustainability criteria in the tendering process for medicinal products; the inclusion of greenhouse gas emissions and impacts on biodiversity in the German supply chain due diligence law; transparent, publicly accessible data on the climate and environmental impacts of new and existing medicines; the reduction of waste and improper disposal; the promotion of generic medicines production in Europe; and training and further education for pharmacists in environmental protection and sustainability.

Environmental impacts of the pharmaceutical sector

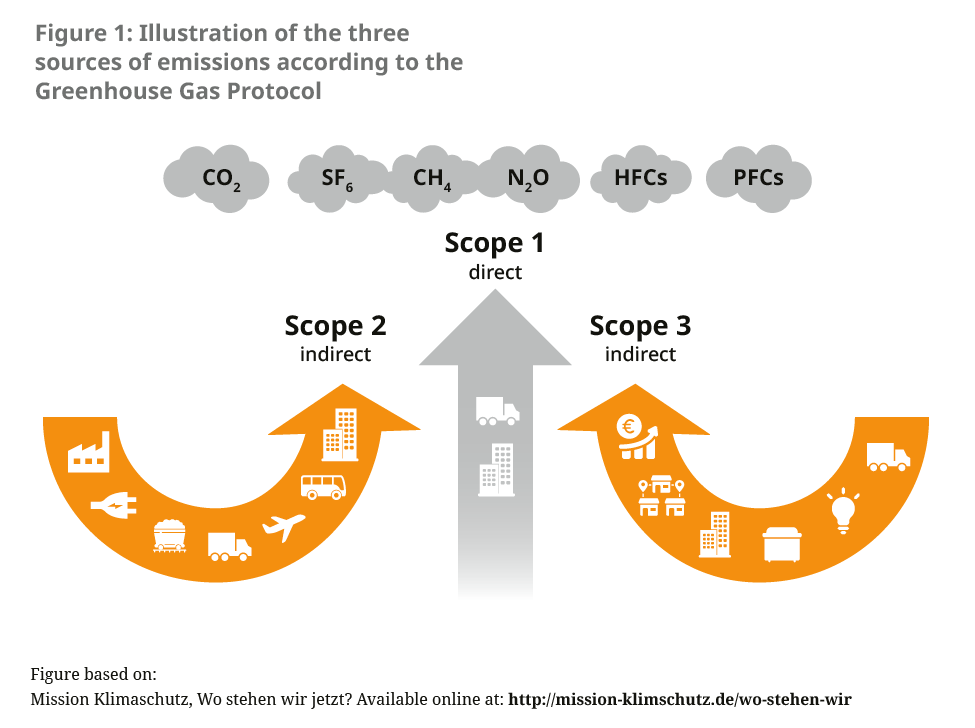

About 5 % of Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions are generated in the health sector.2 There has been no precise recording of the contributions caused by the pharmaceutical sector to date. A reference value can be calculated through comparison with other countries such as England or Austria, which show that medicines and pharmaceutical products account for 20 % of emissions in the health sector.3, 4 Globally, the pharmaceutical industry is thus responsible for more emissions than the automotive industry.5 While an international alliance of pharmaceutical and biotech companies agreed in November 2022 to reduce emissions in their supply chains as part of an “Activate programme”, concrete measures are, for the time being, focused on switching to renewable energy for power supply and more environmentally friendly transport routes.6 The consultancy EcoAct reported in 2021 that 75 % of listed biopharmaceutical companies had reduced their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions and 50 % of their Scope 3 emissions (which account for the majority of emissions in the sector) in the same year, in line with compliance with the 1.5 degree limit (see Figure 1).7

In addition to greenhouse gas emissions, pharmaceutical residues — especially in water — also have an impact on both human health and the environment (often referred to as “ecopharmacovigilance”). According to an analysis by the Federal Environment Agency (UBA), 16 active substances were detected in surface, ground and drinking water in all regions of the world in 2016, above all the painkiller diclophenac — often in ecotoxic concentrations.8 A total of 631 active substances were found in the regions investigated. The official figures only represent part of the actual water contamination, since in many parts of the world there is insufficient measurement data available. Environmental impacts occur throughout the life cycle of a medicine, from production through the supply chain to administration and disposal. Human medicines regularly enter the environment mainly through excretion as well as improper disposal. Although the resulting pharmaceutical residues in water and soil have not yet been classified as hazardous to human health, damages to the ecosystems concerned are considerable and, in some cases, have not yet been adequately investigated.9

Exemplary activities in other countries

In England, the National Health Service (NHS) has developed a roadmap for its suppliers to reach carbon neutrality, which includes a continuous tightening of reporting and emission reduction obligations for current and future suppliers to the NHS.10

Norway, Denmark and Iceland have integrated environmental criteria for the first time in the joint tendering and procurement of medicines, the “Joint Nordic Tendering Procedure”, which entered its second tender in 2022. Suppliers that implement criteria such as environmental certification, a description of environmental guidelines and strategies or environmentally friendly transport are awarded the contract.11 Although it is possible to include environmental criteria in tenders in Germany, the principle of economic efficiency applies first and foremost.i

The Stockholm region in Sweden developed a “Wise List” of medicines between 2017 and 2021, which enables physicians to select the least environmentally harmful product from those with equivalent efficacy.12

Environmental analyses of medicines are also mandatory in the USA. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) takes environmental impacts into account when approving new medicines and can also withdraw approval if new information on environmental damages emerge. Risks to endangered species and their habitats from wastewater generated during production outside the USA must also be assessed.13

New legislative initiatives in Germany and the European Union (EU) and the ongoing revision of existing law offer the potential to improve the regulation of environmental impacts from the pharmaceutical sector.

i In accordance with the principle of economic efficiency anchored in the German Social Code, Book V, the statutory health insurance funds may only cover the costs of services that are sufficient, appropriate and economic — i.e. the most cost-effective — and do not exceed what is necessary.

Green Pharmacy Approach

In order to achieve climate neutrality and practice consistent environmental protection, an all-encompassing “green pharmacy approach” is needed.14 Among other things, this encompasses:

- Considering environmental aspects at the research and development stage of medicines, as well as at the prescribing and disposal stages.

- Giving preference to new substances that are more biodegradable and better absorbed by the human body, while maintaining the same quality and efficacy, in order to reduce permanence in the environment.15

Regulations currently in force in the German pharmaceutical sector

Many players in the sector are already striving for more sustainability and environmental protections within the pharmaceutical sector. Pharmaceutical manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacists and numerous other stakeholders are implementing sustainability goals in their companies, not least through international codes of conduct and supplier contracts, and are thus already going beyond the prescribed level of commitment. However, in order to effectively protect the environment from the continuous exposure of medicinal products, voluntary commitment alone cannot be relied upon. Rather, legal framework conditions are needed to drive innovations towards more sustainability in the pharmaceutical sector. Against this backdrop, it is worth taking a look at the current legal situation in pharmaceutical law in order to uncover weaknesses and identify starting points for the legal anchoring of sustainability and environmental protections.

Environmental protection in pharmaceutical authorisation: A toothless tiger

In addition to the desired effect, pharmacologically active substances often have an environmental relevance.9 Therefore, when applying for a medicinal pharmaceutical authorisation at the European Medicines Agency or the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices in Germany, documents must be submitted on the basis of whether an assessment of possible environmental risks has been carried out.16 This environmental risk assessment has been mandatory under pharmaceutical law for veterinary medicinal products since 1998 and for human medicinal products since 2006. Potentially undesirable effects on the environment are examined.17 If such negative environmental effects are found, however, the consequences for veterinary and human medicines are different: while the authorisation of veterinary medicines can be refused, undesirable environmental risks remain largely inconsequential for the authorisation of human medicines.

Therefore, negative effects on the environment are not included in the risk-benefit assessment to be carried out for the authorisation.18 In the case of identified environmental risks, applicants are only required to include information on the avoidance of these risks in the authorisation application,19 e.g. through reference in the product information, but without any consequences for the marketing authorisation of the drug. The extent to which instructions for use and disposal for the purpose of environmental protection in drug package leaflets are taken into account by consumers has not yet been investigated.

As the authority responsible for the environmental impact assessment of new drug approvals, for years the UBA has been calling for greater regulation and increased transparency around the pharmaceutical industry’s effects on the environment with a view to hold actors legally accountable for environmental violations. Specifically, UBA demands that20

- the environmental risk assessment is strengthened and complemented by mandatory risk mitigation measures;

- the environmental impact of the pharmaceutical industry is regulated within a consistent legal framework covering all relevant regulations and policies;

- uniform production standards be introduced, including greenhouse gas emission limits that can be checked by independent inspectors.

Existing medicinal products without retrospective environmental assessment

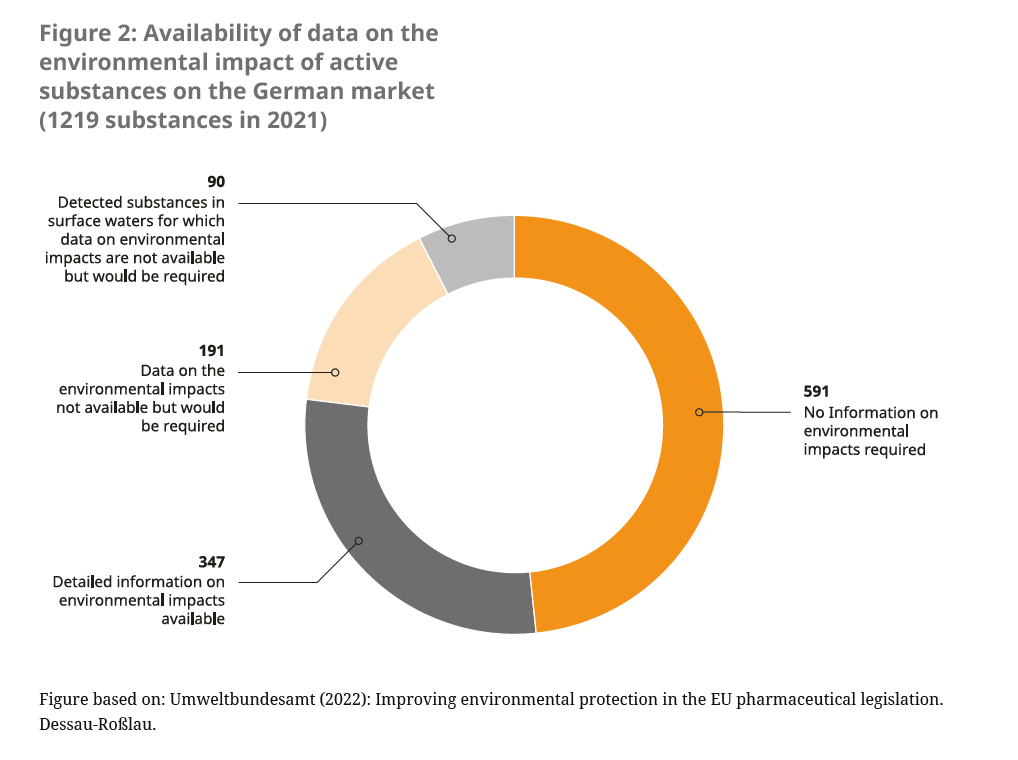

In addition to the lack of consideration of environmental impacts for new pharmaceutical authorisations, medicines that were authorised before the mandatory environmental impact assessment was carried out in 2006 often lack robust data on the environmental balance (see Figure 2). These “old medicines” do not have to retrospectively undergo a post-authorisation environmental impact assessment. There is already a system for recording changes in the benefit-risk ratio,21 the so-called pharmacovigilance system. However, undesirable environmental effects are not recorded there.

The unused potential of chemicals legislation

The identified gaps in pharmaceutical law regarding the regulation of environmental risks are not covered by other legislation. The REACH Regulationii does stipulate that manufacturers and importers of chemicals must assess environmental and health risks themselves and submit corresponding data to the European Chemicals Agency when registering the chemical substance. However, the environmental assessment based on the REACH Regulation does not apply to pharmaceuticals. Substances contained in medicinal products are explicitly exempted from the registration and assessment obligation.22

ii Regulation (EC) 1907/2006 is the European Chemicals Regulation for the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals. “REACH” stands for Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals. As a binding European legal act, it is directly applicable in Germany.

The health risk of strategic dependence

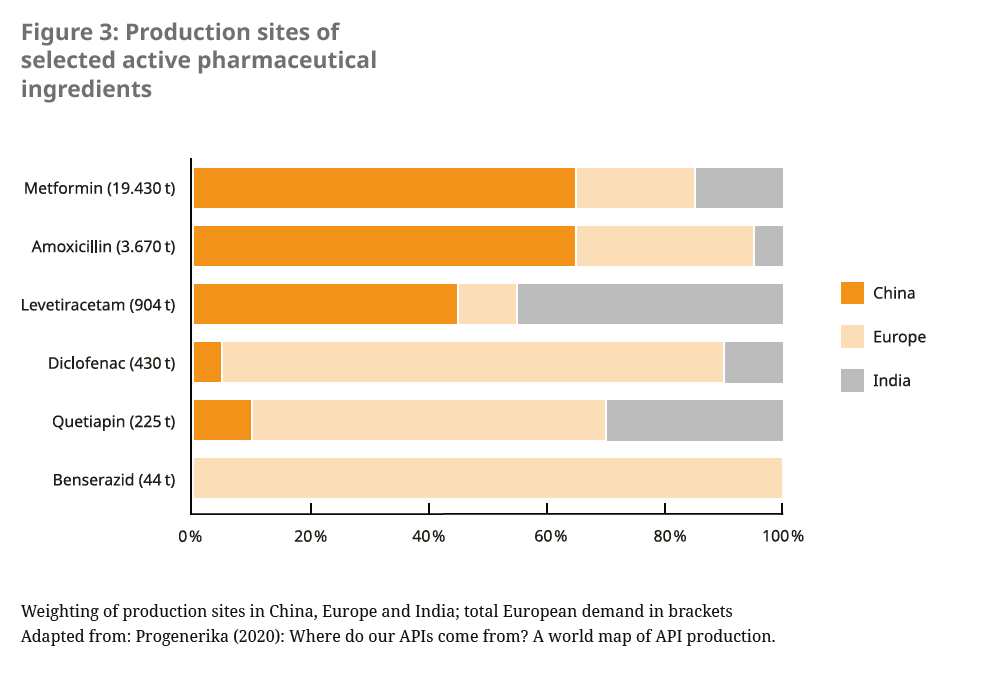

Over the last 20 years, the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) has become increasingly concentrated in a few regions of the world and among a small number of manufacturers.23 In particular, off-patent medicines, including many antibiotics, as well as raw materials and intermediates of many drugs are sourced by European countries mainly from China and India. Some of these international supply chains were disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. The European Commission therefore refers to a “strategic dependence” for these products, which are critical for public health and security of supply.24 It is therefore pursuing efforts to ensure the supply of critical medicines in the future by diversifying production sites, including rebuilding production within the EU.

In order to create incentives for the production of generic medicines, it is also necessary to reconsider the discount contracts between German health insurances and pharmaceutical companies, as these sometimes result in very low prices being paid for generic medicines. This price pressure has contributed to manufacturers lowering production costs as much as possible by producing outside the EU.25

In addition to security of supply, regulation of supply chains in the pharmaceutical sector also offers the potential to improve compliance with environmental and labour standards as well as the protection of natural resources. The German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz — LkSG), which came into force in January 2023, has the potential to improve labour and environmental standards in pharmaceutical production facilities and in supply chains. It initially affects companies that generally have at least 3,000 (1,000 from 2024) employees in Germany.

Environmental impacts are indirectly covered by the LkSG in that harmful soil changes, water and air pollution can constitute human rights risks26 if, for example, they directly damage the natural basis for food production or human health.iii Impacts on the climate or loss of biodiversity are not included though. The LkSG may thus be a first step towards environmental protection in national and international supply chains. However, it needs to be improved with regard to its scope. So far, the Act only applies to a company’s own operations and direct suppliers, whereas for indirect suppliers, the company must only conduct a risk analysis in circumstances where there has been a suspected or confirmed violation of environmental law. Moreover, a violation of the due diligence obligations of the LkSG does not automatically give rise to any civil liability; rather, legal enforcement remains with the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA), which can penalise violations as administrative offences.

iii The LkSG provides direct coverage of environment-related risks – without concrete reference to human rights risks – with regard to the avoidance of long-lived pollutants (Stockholm Convention), the avoidance of mercury emissions (Minimata Convention) and the control of transboundary movements of hazardous wastes (Basel Convention).

While the LkSG defines its scope of application independently of the sector through companies’ number of employees, the European Commission’s current draft Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive also defines so-called “high-impact” sectors, which are particularly prone to violations of human rights and environmental concerns (see explanatory memorandum p. 18 of the draft directive).27 Currently, the pharmaceutical sector does not fall under the defined high risk sectors. For a broader scope of supply chain regulation, the pharmaceutical sector should be included.

Pharmacies as the lever for health and environmental protection

Dispensing points such as pharmacies have great influence on the adequate handling and disposal of medicines and can thus reduce the routes of entry of pharmaceuticals into the environment. Pharmacists, as the direct contacts of the end users, play an essential role here. It is the professional duty of pharmacists to inform and advise patients28 including on the proper storage and disposal of medicinal products.29

This duty to provide advice does not, however, extend to information on the environmentally conscious handling and disposal of medicinal products with environmental relevance. Where possible, pharmacists could advise customers on which medicines are to be preferred for environmental reasons. Limits to pharmacists’ advice are, however, found in the medical freedom of therapy, which is not supposed to be influenced by the pharmacist.30 Secondly, expert advice on the environmental effects of medicinal products presupposes prior knowledge, which would have to be ensured through education and training.

Some medical societies in Germany have already developed guidelines that take into account the environmental impact of various medical products. These include, for example, the recommendation for the climate-friendly prescription of inhaled medicines from the German Society for General and Family Medicine.31

Pharmacies could also have a decisive influence on disposal. According to the current legal situation in Germany, the return of unused medicines by pharmacies is purely a voluntary service. Customers are neither obliged to take back their unused medicines, nor do they have a right to do so. Until 2009, the disposal of old medicines via pharmacies was regulated nationally. However, this sensible regulation was discontinued as a result of an amendment to the Packaging Act with the discontinuation of a collection system free of charge for pharmacies.32 A new, consistent regulation could be introduced by the EU Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), which could have an effect together with the targeted education of end consumers on the proper disposal of medicinal products.

Sustainable management and environmental protection are also taking on an increasingly important role in the pharmacy landscape. At the beginning of 2022, the Federal Union of German Associations of Pharmacists (ABDA) mentioned sustainability and climate protection in the preamble of its resolution on “Pharmacy 2030”, but did not elaborate on these aspects.33 In September 2022, “Climate Change, Pharmacy and Health” was a key theme of the German Pharmacists’ Conference 2022. Seven relevant motions were adopted, dealing with measures to make pharmacies and the ABDA work more sustainably and including the following core demands for the profession:34

- Climate-friendly redesign of pharmacies’ ways of working

- Integrating the health consequences of climate change into initial, further and continuing education and training

- Advice from pharmacists to patients on the health consequences of climate change

- Commitment by the professional associations of pharmacists to include more comprehensive climate protection measures in pharmacies

Whilst these developments within Germany are important, the sector often points out that regulations at EU level would be needed to anchor sustainability in law.

Starting points for new European and national strategies

The European Commission’s reform efforts could remedy the current deficiencies in the regulation of medicinal products. The Medicines Strategy for Europe 2020 aims to ensure the quality and safety of medicines and to increase the transparency and security of supply chains. The aim of this initiative is to propose and develop a regulation to revise the current EU pharmaceutical regulations.35 Within this framework, the requirements for environmental risk assessment and conditions of use for medicinal products are to be strengthened.

In addition to the new pharmaceutical strategy at European level, there is a government draft for a new national water strategy for Germany. This provides for considerable improvements in the control and reduction of pollutants in the German water supply. It is intended to implement the EU’s Zero Pollutant Action Plan across all sectors and to strengthen chemicals management. Among other things, threshold values for human and veterinary medicines are to be introduced in groundwater supplies by 2030 and a new database for chemical substances is to be established, which will create transparency and enable follow-up controls.36

In order to effectively establish the necessary environmental and climate protections in the pharmaceutical sector, several windows of opportunity are opening up for legislators at federal and EU level, as well as for actors in the pharmaceutical sector, as outlined in this policy brief.

Recommended actions for legislators at federal and EU level and the pharmaceutical sector

Faced with the urgency of our ecological crises, to improve sustainability and climate protection in the entire pharmaceutical sector, legislators must act with the following options:

- Authorisation-relevant environmental risk assessment for all medicinal products for human use with binding risk reduction measures in medicinal products law at national and European level: In the interplay of chemicals and medicinal products law, there is a need for the inclusion of environmental effects in the authorisation regime of medicinal products for human use or their active substances in the European Directive 2001/83/EC (Community Code for Medicinal Products for Human Use) and in the German Medicinal Products Act.

- Mandatory consideration of sustainability criteria in the tendering process for medicinal products: To this end, sustainability should be integrated into the German Social Code.

- Inclusion of greenhouse gas emissions and impacts on biodiversity in the Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains: The law should be expanded to include these essential dimensions and provided with clear, evidence-based criteria.

- Transparent, publicly available data on the climate and environmental impacts of new and existing medicines: These data should be publicly available and evidence-based thresholds should be set to limit damage to ecosystems.

- Reduction of wastage and improper disposal: Better education of pharmacists, health professionals and patients on the proper disposal of medicines and an expansion of take-back points for medicines in pharmacies is desirable.

- Support for the production of generic medicines in Europe: In order to ensure security of supply, especially for antibiotics, in Germany, and to have transparent information and control over production conditions as well as to save emissions, stricter requirements should be adopted with regard to discount contracts for generics and/or targeted support for the production of generics in Europe introduced.

- Education and training for pharmacists with regard to environmental protection and sustainability: Both pharmacy students and already qualified pharmacists should be trained in the handling of environmentally hazardous medicinal products. In addition, information on environmental risks of medicinal products urgently need to be made more publicly accessible so that pharmacists can inform themselves about changes in environmental risks.

In order to protect health, the climate and the environment, these changes in the regulation of the pharmaceutical sector should be implemented as quickly as possible at the federal and EU levels. Stakeholders in the pharmaceutical sector can and should continue to play an important role in this regard and take greater responsibility and opportunities for action.

References

- German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU) (2021). Planetary health: What we need to talk about now. Berlin: German Advisory Council on Global Change.

- Health Care Without Harm (2019). Health care’s climate footprint.

- NHS England (2022). Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service.

- Weisz U. et al. (2019). The carbon footprint of the Austrian health sector. Final Report. Vienna: Climate and Energy Fund, Austrian Climate Research Programme.

- Belkhir L. & Elmeligi A. (2019). Carbon footprint of the global pharmaceutical industry and relative impact of its major players. Journal of Cleaner Production 214, 185–194.

- Manufacture 2030 (2022). Activate program launched to accelerate decarbonization in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) supply chains.

https://manufacture2030.com/insights/news/2022/11/activate-program-launched-to-accelerate-decarbonization-in-active-pharmaceutical-ingredient-api-supply-chains - EcoAct (2021). The Climate Report and Performance of the DOW 30, EURO STOXX 50 and FTSE 100.

https://info.eco-act.com/hubfs/0%20-%20Downloads/SRP%20research%202021/Climate-reporting-performance-research-2021.pdf - Aus der Beek T. et al. (2016). Pharmaceuticals in the envrionment: Global occurance and potential cooperative action under the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM). Federal Environment Agency.

- Federal Environment Agency (2014). Pharmaceuticals in the environment. Federal Environment Agency.

- NHS England (n.d.). Net zero supplier roadmap.

https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/get-involved/suppliers/ - Amgros (2022). Second Joint Nordic Tendering Procedure for medicines complete.

https://amgros.dk/en/knowledge-and-analyses/articles/second-joint-nordic-tendering-procedure-for-medicines-completed/ - Stockholm Region (n.d.). Information on environmental effects of medicinal products.

https://janusinfo.se/beslutsstod/lakemedelochmiljo.4.72866553160e98a7ddf1d01.html - Walter S. & Mitkidis K. (2018). The Risk Assessment of Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: EU and US Regulatory Approach. European Journal of Risk Regulation 9(3), 527–547.

- Daughton C.G. (2003). Cradle-to-cradle stewardship of drugs for minimizing their environmental disposition while promoting human health. I. Rationale for and avenues towards a green pharmacy. Environmental Health Perspectives 111(5).

- Kümmerer K. & Hempel M. (2010). Green and sustainable pharmacy. Springer.

- Arzneimittelgesetz (2012). § 22 Zulassungsunterlagen Abschnitt 3c.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/amg_1976/__22.html - Krüger, C. in Kügel, J.W. et al. (2022), Arzneimittelgesetz, 3rd edition 2022, § 4 marginal no. 295.

- Arzneimittelgesetz (2012). § 4 Sonstige Begriffsbestimmungen Abschnitt 28.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/amg_1976/__22.html - Arzneimittelgesetz (2012). § 22 Zulassungsunterlagen Abschnitt 3c.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/amg_1976/__22.html - Gildemeister D. et al. (2022). Improving environmental protection in EU pharmaceutical legislation. Federal Environment Agency.

- Arzneimittelgesetz (2012). § 63b Allgemeine Pharmakovigilanz-Pflichten des Inhabers der Zulassung.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/amg_1976/__22.html - Directive 2006/121/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to the classification, packaging and labelling of dangerous substances in order to adapt it to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) and establishing a European Chemicals Agency. II: Registration of substances, section 5 lit. A.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006L0121&from=EN - Progenerics (2020). Where do our APIs come from? A world map of API production.

- European Commission (2021). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Strategic Perspectives 2021 — The EU’s capacity and freedom to act.

https://dserver.bundestag.de/brd/2021/0726–21.pdf - Bundesverband der pharmazeutischen Industrie e.V. (2022). Production of pharmaceuticals.

https://www.bpi.de/de/themendienste/produktion-von-arzneimitteln - Gesetz über die unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichten zur Vermeidung von Menschenrechtsverletzungen in Lieferketten (2022). § 2 Begriffsbestimmungen, Abschnitt 2, Nummer 9.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/lksg/__2.html - European Commission (2022). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on corporate due diligence with regard to sustainability and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937.

- Verordnung über den Betrieb von Apotheken (Apothekenbetriebsordnung — ApBetrO) (2012). § 20 Information und Beratung, Abschnitt 1.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/apobetro_1987/inhalts_bersicht.html - Verordnung über den Betrieb von Apotheken (Apothekenbetriebsordnung — ApBetrO) (2012). § 20 Information und Beratung, Abschnitt 2.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/apobetro_1987/inhalts_bersicht.html - Verordnung über den Betrieb von Apotheken (Apothekenbetriebsordnung — ApBetrO) (2012). § 20 Information und Beratung, Abschnitt 1a.

https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/apobetro_1987/inhalts_bersicht.html - German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) (2022). Climate-conscious prescription of inhaled medicinal products.

- Wessinger, B. (2018, March 22). Altarzneimittel gehören in die Apotheke! [Existing medicines belong in the pharmacy!] Deutsche Apothekerzeitung.

https://www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/news/artikel/2018/03/22/altarzneimittel-gehoeren-in-die-apotheke - Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände e.V. (2022). Apotheke 2030: Perspektiven zur pharmazeutischen Versorgung in Deutschland (2.0).

- ABDA (2022). Resolutions of the General Meeting of German Pharmacists.

https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/DAT_Beschluesse/DAT_2022_Beschluesse.pdf - European Commission (2020). Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe.

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (2022). Government draft of the National Water Strategy.

https://www.bmuv.de/download/regierungsentwurf-nationale-wasserstrategie

© CPHP, 2023

All rights reserved.

Centre for Planetary Health Policy

Cuvrystr. 1, 10997 Berlin

info@cphp-berlin.de

www.cphp-berlin.de

Citation suggestion: Baltruks D., Sowa M., Voss M. (2023). Strengthening sustainability in the pharmaceutical sector. Policy Brief 01–2023. Berlin: Centre for Planetary Health Policy. Available from: https://cphp-berlin.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/CPHP_Policy-Brief_01-2023-en.pdf

CPHP publications are subject to a three-step internal review process and reflect the views of the authors.