Open questions for policymakers, scientists and health actors

Dorothea Baltruks, Sophie Gepp, Remco van de Pas, Maike Voss, Katharina Wabnitz

Policy-Brief 01–2022

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7524587

To address the urgent planetary crises and to ensure the planet’s habitability for future generations, planetary health needs to be anchored as a vision in all policies at national and international levels. Experiences and lessons learned from other policy fields and other countries can be considered in strengthening prevention of and preparedness for planetary crises and their health risks. To do so, we need to answer some urgent questions: 1) how can regulatory frameworks, structures, institutions, and incentives be adapted to make health within planetary boundaries the core goal of a comprehensive prevention policy and a public welfare-oriented care economy? 2) what role do conflicting goals and interests play in this context? 3) how can health equity and environmental justice be integrated into (health) policy decisions? 4) what forms of science communication, translation and generation are needed to accelerate the transformation towards health within planetary boundaries effectively?

Healthy people only exist on a healthy planet

Looking at the global development of human health in recent decades, a contradictory picture emerges: on the one hand, life expectancy – one of the main indicators of well-being – has risen and the proportion of undernourished people has tended to decline.1,2 On the other hand, this progress on health remains unevenly distributed both within and across countries and population groups.3

While deaths from communicable diseases are decreasing globally, non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases are rapidly increasing in all countries.4 The regional differences in the distribution of health and social advancements are significant but come at a high price: they endanger the habitability of the planet. In particular, the use of fossil fuels for energy generation and its impact on global warming but also changes in land and water use – especially for food production, the expansion of housing and infrastructure, the overexploitation of natural resources, the pollution and destruction of ecosystems and the associated loss of biodiversity are causing the overshooting of multiple planetary boundaries as well as human rights violations.5,6 We are amidst multiple, escalating, systemic crises, both within natural and human systems. We describe these multidimensional crises that partially reinforce each other as planetary crises.

A safe scope and just scope for human well-being

To protect health and to preserve the habitability of the planet for future generations, planetary boundaries must not be exceeded any further. At the same time, the consequences of overshooting certain boundaries must be mitigated and reversed as far as possible. The medical journal, The Lancet, has identified the climate crisis as humankind’s greatest threat7 and its tackling as a major opportunity for human health and well-being in the 21st century.8 Regarding the transgression of the planetary boundary “climate change”, the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is clear:

“The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”9 The same can be said for other planetary boundaries.

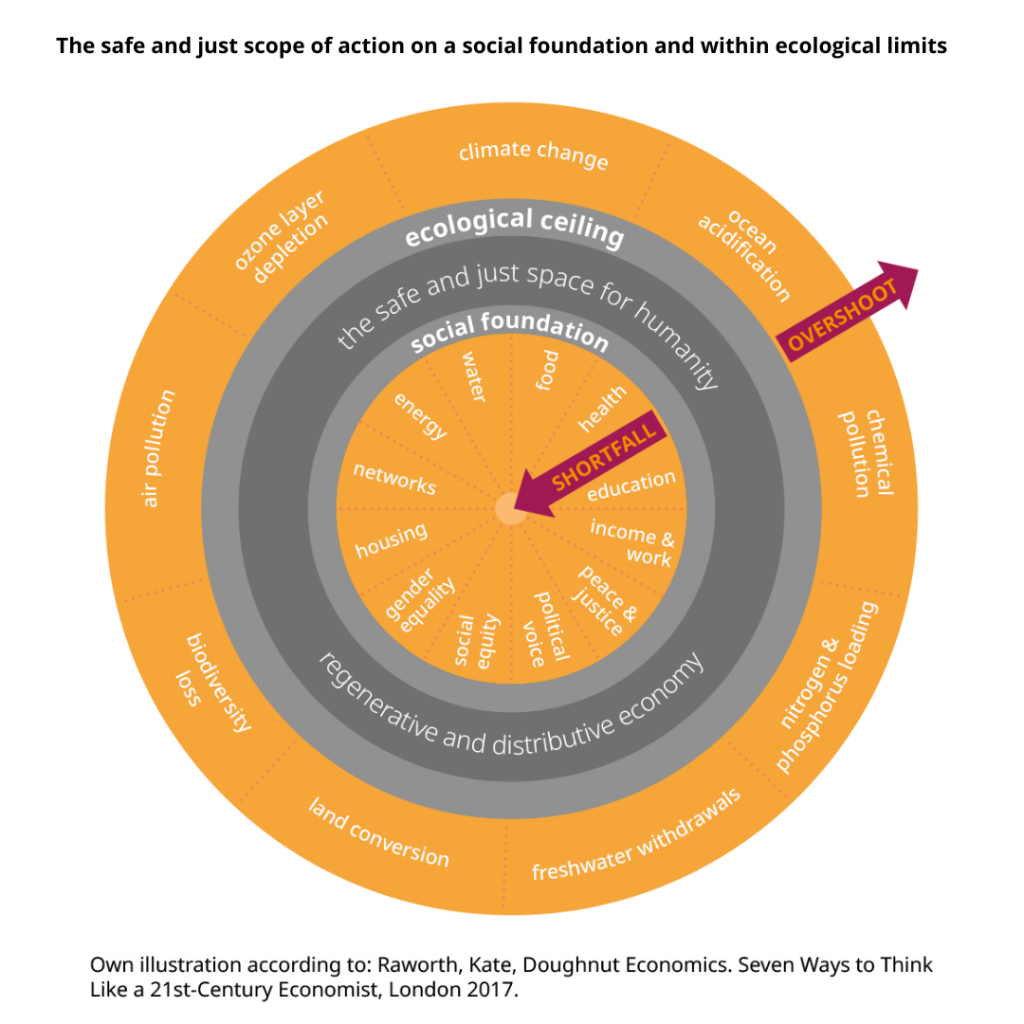

The ‘safe and just space for humanity’ that is based on a comprehensive social foundation but does not transgress the ecological ceiling of the Earth’s natural systems is visualised by Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics model (see Figure 1).10 It illustrates what the global economic system must achieve: the attainment of minimum social standards for all without exceeding planetary boundaries.11 These include meeting basic needs but also access to high quality education, work and health care.

Political, social, and economic processes and structures must therefore be designed and governed nationally, as well as internationally, with a focus on safeguarding health and well-being for present and future generations while also preserving the habitability of the planet.

The well-documented health effects of the planetary crises range from acute physical and psychological burdens caused by extreme weather events, the emergence and spread of new (zoonotic) infectious diseases, the effects of air pollution on various organs, to food insecurity and forced migration.12,13,14 The exceeding of planetary boundaries affects us all, but not equally: disadvantaged and marginalised population groups in all regions of the world are most affected by these impacts, even though they have contributed least to their creation.

The richest 10% of the world’s population cause half of global greenhouse gas emissions and pose major challenges to global burden sharing.15 The consequences of planetary crises thus reinforce historical and persistent marginalisations, poverty risks, conflicts and thereby inequalities such as colonial continuities and gender inequities.16 Although these increasing risks to human health, stability and security are politically known, one question in particular remains: how can political, economic, and social systems deal with these risks in a forward- looking manner? If these risks were significantly reduced now and investments were made in prevention and crisis preparedness, a societal transformation could lead to more resilience and

health equity. To achieve this, the principle of prevention helps as a political compass.17 To make use of this compass, profound changes are needed to human activities, in the form of a „societal transformation“, as recently carried out by the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU).18

We do not lack knowledge of the health consequences we face from multiple systemic crises nor know-how on how to overcome them. There is also no lack of compelling visions for the future. However, there is a lack of concrete and effective political activity to ensure the required transformation at all levels and across national borders to secure health within planetary boundaries.19

Challenges for the German health system posed by planetary crises

Our health system is part of an unsustainable social and economic system. The paradigm of growth, which manifests in the need to constantly increase gross domestic product (GDP), is not expedient for designing a sustainable social and economic system for planetary health.21 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), GDP is a widely used but in (planetary) health terms, it is an inappropriate tool for measuring economic activities, as it largely excludes their environmental and health impacts and immaterial values.22

A societal debate on how health and wellbeing can be created within planetary boundaries and what the health system should do and should not do to achieve this, is urgently needed but so far lacking. This also includes considering how the access, quality and financing of a climate- neutral health system can be realised in accordance with the doughnut economics model.23 The health system has a special role to play in the transformation. On the one hand, 4.4% of the world’s24 and 5.2% of Germany’s national25 greenhouse gas emissions are produced by the health system and while it’s not the largest source of emissions, it is an important driver of the climate crisis nonetheless. Simultaneously, the overlapping planetary crises create additional and often preventable burdens of disease that pose enormous challenges to the health system, both now and in the future.26 For all actors in the health sector, the principle ‘Do no harm’ applies, which must be widened in the Anthropocene. Harm to the environment must be avoided to safeguard (planetary) health, and prevention must be prioritised over cure.27

This results in the need for a comprehensive prevention policy. Although the goal of promoting and maintaining health already guides actions and is internalised by health professionals, the regulatory framework, incentives and in some cases institutions that prioritise and implement health prevention and promotion are lacking.28 This currently prevents health actors from taking transformative action in their own institutions.

The German Social Codes (Sozialgesetzbücher) currently prescribe principles such as quality of and access to health services as well as their economic efficiency as legal frameworks in the provision of services. Sustainability (meaning both ecological sustainability and health equity) is not yet sufficiently considered, despite being indispensible from a planetary health perspective.29 Political decision-makers, legislators at federal and state level as well as the bodies of self-administration that play a central part in the governance of the German health system have a central responsibility to adapt the regulatory framework and to set effective incentives. In addition, the health system is not sufficiently prepared for future system shocks such as extreme weather events,30 the care of people nationally or internationally displaced due to planetary crisis, nor for outbreaks of infectious diseases with pandemic potential.31 This lack of preparation represents a real risk in the case of heatwaves, which represent the greatest climate change-related health risk in Germany.32 Extreme hot days require a cross-policy field approach to ensure that care can be provided in the event of a crisis and to strengthen the resilience of the health system.

Planetary health

The effects of human activities on political, economic, and social systems in the 21st century represent the greatest factor influencing the natural environment as well as human and animal health. The environment can do without us — but we cannot do without it. „As living beings, we humans are an inseparable part of nature and, despite all technical achievements, we are ultimately dependent on it“, as the WBGU put it in its impulse paper.18

The concept of planetary health encompasses a broad, transdisciplinary understanding of the factors and conditions for human health today and in the future. To protect and promote health within planetary boundaries, the Earth’s natural systems and processes are indispensable, as they create favorable living conditions for human well-being and health, as are political, social, and economic systems that enable equity. In achieving planetary health, the planetary boundaries will no longer be exceeded, and all people will be enabled to live healthy, dignified, and secure lives within effective and sustainable political, social and economic systems.

Anthropocene

The ‘Anthropocene‘ is a term used to describe the human-dominated epoch that is characterised by profound changes in Earth systems as a result of human activities. These include the increased amount of manufactured materials in sediments, the alternation of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous cycles, climate change and resulting sea-level rise as well as the accelerated rate of species extinction.20

Challenges for the governance of planetary health outside the health system

To achieve planetary health, new forms of political governance and design are required that extend beyond health policy. Since the greatest health gains and losses are caused by structural determinants and are thus independent of healthcare33, new forms of governance for planetary health are needed in other policy fields. Health governance within planetary boundaries describes all institutionalised forms of social coordination that: 1) aim to develop and implement binding rules for ensuring health and well-being 2) aim to provide collective goods for the benefit of society without exceeding planetary boundaries.34

Policies that aim to achieve planetary health are characterised by systems thinking and the consideration of path dependencies. This approach aims to address the adverse health impacts of past policy decisions. To advance the transformation of the German health system, change in other sectors — especially the energy system — is indispensable. The transformation of the energy system would have far-reaching positive effects on other policy areas and would simultaneously contribute to a significant reduction in the burden of disease, for example by reducing air pollution. The WHO estimates that air pollution causes about 33% of new cases of childhood asthma, 17% of all lung cancers, 12% of all heart attacks and 11% of all strokes in Europe.35 At the same time, the use of fossil fuels is the biggest driver of the climate crisis.36

This example illustrates the interconnectedness of individual sectors and how their transformation would have direct and indirect positive impacts on health. The use of renewable energy sources is not only good for the climate, but also promises so-called co-benefits for population health.37 It will be relevant for prevention policy in the future to develop co-benefit policies in a targeted manner and to reduce the effects and costs of other policy areas at the expense of health.

In transport policy, for example, the health costs of environmental, air and noise pollution and greenhouse gases could accelerate the transformation of this sector. The global interconnectedness and interdependencies of countries and regions as well as the global nature of planetary crises show that the strict distinction between foreign or development and domestic policy is obsolete when it comes to the governance of planetary health. From a health perspective, the implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement is an essential measure to promote health globally.38 To comply with the Paris Agreement as well as further international agreements concerning other planetary boundaries, the historical responsibility of states for planetary crises must be recognised and the adaptation and mitigation measures must be financed accordingly. In addition, a solidary approach to dealing with climate-related losses and damages must be found, which is a key element of the concept of ‘climate justice’.39,40 For the analysis of global health governance within planetary boundaries, it is crucial to determine who sits at the table, with which resources and in which power constellations, and who does not.

States of the Global North and the Global South, their civil societies, science and (transnational) companies can jointly shape, accelerate or deliberately obstruct the necessary transformation. But the forms of governance and cooperation at levels which are helpful and necessary for achieving planetary health have not yet been sufficiently described.41

Open questions for policymakers, scientists and health actors

To ensure a resilient, high quality, accessible, environmentally friendly, and fundable health system for all and for future generations within a public welfare, health-promoting and preventive framework, the following questions must be answered:

- Agenda-Setting

How can planetary health as a vision for the future be established as a standing item on national and international political agendas permanently and effectively? - Crisis prevention and preparedness

How can ecological and social risks to the health of current and future generations be decreased and what can be learned from other policy fields and countries? - Governance

What new forms of governance reforms, institutions, structures and incentives are needed for a prevention policy and a public welfareoriented care economy that aims to safeguard health within planetary boundaries? - Partnerships

What kind of partnerships are necessary for planetary health and how are conflicts of interest between actors that hinder or even block the transformation towards planetary health negotiated? - Equity

How can health equity and environmental justice be incorporated in (health) policy decisions? - Participation

How can the perspectives of health actors and those most affected by the impacts of the transgression of environmental and social boundaries be integrated in policy processes? - Communication

What forms of science communication, translation and generation are needed to effectively accelerate the transformation towards health within planetary boundaries?

List of references

- Max Roser, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Hannah Ritchie. „Life Expectancy“. 2013 [cited 2022 June 8]; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy.

- Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie. „Hunger and Undernourishment“. 2019 [cited 2022 June 8]; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/hunger-and-undernourishment.

- Conceição, P., Human development report. 2019: beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: inequalities in human development in the 21st century. 2019.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Results. 2020 [cited 2022 May 31]; Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Annalisa Savaresi and Marisa McVey, HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES BY FOSSIL FUEL COMPANIES. 2020, 350.org.

- O’Neill, D.W., et al., A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability,2018.1(2):p.88–95.

- Costello, A., et al., Managing the health effects of climate change: lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. The lancet, 2009. 373(9676): p. 1693–1733.

- Watts, N., et al., Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. The Lancet, 2015. 386(10006): p. 1861–1914.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chance (IPCC), Summary for Policymakers, in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, D.C.R. H.-O. Pörtner, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem„ Editor. 2022: Cambridge University Press. In press.

- Schlüter K., et al., Die Donut-Ökonomie als strategischer Kompass Wie kommunale Strateginnen und Strategen die Methoden der Donut-Ökonomie für die wirkungsorientierte Transformation nutzen können, in pd Impulse. 2022, PD — Berater der öffentlichen Hand GmbH.

- Raworth, K., Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. 2017: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Myers, S. and H. Frumkin, Planetary health: Protecting nature to protect ourselves. 2020: Island Press.

- Romanello, M., et al., The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10311): p. 1619–1662.

- Traidl-Hoffmann, C., et al., Planetary Health: Klima, Umwelt und Gesundheit im Anthropozän. 2021: MWV.

- Gore, T., Confronting Carbon Inequality: Putting climate justice at the heart of the COVID-19 recovery. 2020.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chance (IPCC), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. D.C.R. H.-O. Pörtner, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V.

Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama,. 2022, Cambridge University Press. In Press. - Bourguignon Didier. The precautionary principle: Definitions, applications and governance. 2015 [cited 2022 June 8]; Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_IDA(2015)573876.

- Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen (WBGU),

Planetare Gesundheit: Worüber wir jetzt reden müssen 2021. - Whitmee, S., et al., Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet, 2015. 386(10007): p. 1973–2028.

- Hensher, M. and K. Zywert, Can healthcare adapt to a world of tightening ecological constraints? Challenges on the road to a post-growth future. bmj, 2020. 371.

- The WHO Council on the Economics of Health for all, Valuing Health for All: Rethinking and building a whole-of-society approach, in Council Brief. 2022.

- Jackson, T., Post growth: Life after capitalism. 2021: John Wiley & Sons.

- Lenzen, M., et al., The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2020. 4(7): p. e271-e279.

- Karliner, J., et al., HEALTH CARE’S CLIMATE FOOTPRINT HOW THE HEALTH SECTOR CONTRIBUTES TO THE GLOBAL CLIMATE CRISIS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR ACTION, in Climate-smart health care series. 2019.

- Mayhew, S. and J. Hanefeld, Planning adaptive health systems: the climate challenge. The Lancet Global Health, 2014. 2(11): p. e625-e626.

- Wabnitz K. and Wild V., Ärztliches Ethos im Anthropozän, in Heidelberger Standards der Klimamedizin, N. C, Editor. im Erscheinen.

- Bödeker, W. and S. Moebus, Ausgaben der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung für Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention 2012–2017: Positive Effekte durch das Präventionsgesetz? Das Gesundheitswesen, 2020. 82(03): p.282–287.

- Wagner, O.J.U., Tholen, L., Bierwirth, A.„ Zielbild: Klimaneutrales Krankenhaus, in Abschlussbericht. 2022, Wuppertal Institut.

- Bode, I., 16 Den Klimawandel bewältigen: Herausforderungen an die institutionelle Organisation des Gesundheitswesens.

- Hanefeld, J., et al., Towards an understanding of resilience: responding to health systems shocks. Health Policy and Planning, 2018. 33(3): p. 355–367.

- Günster, C., et al., Versorgungs-Report. 2019: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

- World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. 2022 [cited 2022 June 8]Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

- Börzel T A., Risse T., and Draude A., Governance in areas of limited statehood, in The Oxford handbook of governance and limited statehood. 2018.

- Hanna Yang, et al., NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASES AND AIR POLLUTION. 2019, World Health Organization (WHO).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chance (IPCC), Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, B. Zhou„ Editor. 2021: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, In press.

- Haines, A., Health co-benefits of climate action. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2017. 1(1): p. e4-e5.

- Hamilton, I., et al., The public health implications of the Paris Agreement: a modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2021. 5(2): p. e74-e83.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Introduction to Climate Finance. 2022[cited 2022 June 8]; Available from: https://unfccc.int/topics/climate-finance/the-big-picture/introduction-to-climate-finance.

- Climate Analytics. Loss and damage. 2022 [cited 2022 June 8];Available from: https://climateanalytics.org/briefings/loss-and-damage/.

- de Paula, N., Planetary health diplomacy: a call to action. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2021. 5(1): p. e8-e9.

- Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen (WBGU), Welt im Wandel: Gesellschaftsvertrag für eine Große Transformation. 2011: Berlin.

© CPHP, 2022

All rights reserved.

Centre for Planetary Health Policy

Cuvrystr. 1, 10997 Berlin

info@cphp-berlin.de

www.cphp-berlin.de

Citation suggestion:

Baltruks D., Gepp S., Van de Pas R., Voss M., Wabnitz K. Health within planetary boundaries. Policy Brief 01–2022. Berlin.

Available from: www.cphp-berlin.de

CPHP publications are subject to a three-step internal review process and reflect the views of the authors.

Disclaimer:

Authors in alphabetical order.

Contact: Maike Voss

maike.voss@cphp-berlin.de